Put a Pin on it: Resurrection City Reflections

Earlier this semester, I blogged about my group’s final project proposal on interpreting Resurrection City. As a means of narrowing the scope of our overall workload for the semester, Joanna, Kristen, and I planned to complete our History and New Media final project in conjunction with that of our Public History Practicum course. Partnering with the National Park Service, our Practicum group worked to produce a webpage wireframe interpreting the events of the Poor People’s Campaign and the Resurrection City experience. For our New Media portion, we initially intended to create a Resurrection City mobile application (or at least a mock-up of one) to supplement the interpretation presented on our Practicum webpage. As the semester progressed, however, the group ultimately determined that going a different digital route might serve to interpret Resurrection City and the Poor People’s Campaign in a better manner.

Bird’s Eye View of Resurrection City, early summer 1968. (Billy E. Barnes Negative Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill).

Spending several class periods examining the various platforms available within the new media realm, we gained a clearer understanding of the potential pitfalls associated with mobile applications. At the forefront of these concerns lay the shared acknowledgement between group members of a substantial lack in technical skills to produce an application at the high level of quality required for a successful project. In looking at other project formatting options, Stephen Robertson’s article on spatial mapping in the digital age, “Putting Harlem on the Map,” particularly resonated with us. Recounting his experience in using digital tools to present research findings on a study of everyday life in 1920s Harlem, Robertson highlights the visual properties of such media as one of the “core properties” of digital history. Traditionally, maps used for historical study have always provided a visual aspect to scholarly research. With the onset of the digital age, the use of mapping technology in new media works allow for an increased level of interactivity with the scholarship. Relationships and patterns revealed through spatial mapping, for Robertson’s project in particular, “prompted questions..and facilitated comparisons” that might otherwise not received consideration from the project’s researchers. This in turn allowed for project developers to present to their audience “a new perspective” on Harlem’s past.

This focus on the visual and the opportunity to alter perceptions of the past made spatial mapping seem to us an ideal forum within which to work on our own project. With a primarily audio-visual source base, and largely deemed within the existing historiography as a failure, Resurrection City and the Poor People’s Campaign today form an oft-looked over piece of civil rights history. Hoping to raise awareness of the 1968 demonstration and highlight the campaign’s more successful aspects, we chose to focus our project on the themes of community and interpersonal relationships, movement and mobilization, & shared space and public dialogue.

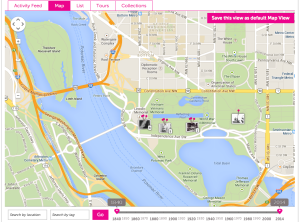

Deciding that a spatial mapping project appeared the best option for the new media component of our project, we eventually settled on HistoryPin as an ideal platform through which to present our final product. A contributor-based site powered by spatial mapping technology in partnership with GoogleMaps, HistoryPin allows users to publicly upload images and “pin” them to specific points on an interactive global map. To share these images and the stories associated with them, users have the option to combine content to create and curate their own online tours and collections. As mentioned on the site’s “About” page and introductory video, this capacity for interactivity and connectivity make HistoryPin

“a way for millions of people to come together, from across different generations, cultures and places, to share small glimpses of the past and to build up the huge story of human history.”

To take full advantage of HistoryPin’s offerings in presenting an in-depth interpretation of Resurrection City and the Poor People’s Campaign, our group ended up splitting our project into two portions. Joanna chose to focus on the community mobilization and movement of PPC participants as they marched from across the country towards Washington, D.C., creating a tour examining their various journeys. Meanwhile, Kristen and I worked together to compile a collection of images depicting the Resurrection City encampment and demonstrations on the National Mall and surrounding areas.Emphasizing our “big idea” theme of community, we selected a series of photographs we believe best reflected the community spirit felt by Resurrection City residents along with how that communal bond shone through during the numerous marches and rallies held by demonstrators at the time.

To do this, we created a HistoryPin channel linking to our #historyAU Twitter accounts that served as a holding basin of sorts for all of our pinned content and through which we could build a collection from selected images. After uploading our images onto the channel, we added captions and interpretive labels to each one along with the appropriate source citation information. Then, we pinned each of the photographs to the National Mall and surrounding locations on the Google-powered HistoryPin map. After completing these basic steps we were able to combine all of our images into a single collection, through which users can view them as a group slideshow or on an individual level. Additionally, collection viewers can use the map function to examine Resurrection City’s location on the National Mall and are free to add comment and suggestions on the collection and content.

As a digital tool, HistoryPin proved relatively simple to learn and easy to use in creating our collection — although there were some slight hiccups along the way. With the site’s provided bulk uploader intended for collections consisting of 200 images or higher, the task of individually uploading and pinning each of our 17 images manually ended up taking a significant chunk of time (around five hours to upload all of them in one sitting). Additionally, HistoryPin offers an interesting “Streetview” feature which, when enabled, allows users to view pinned content with the older image overlaid onto a current view of the site through GoogleMaps satellite imaging. While definitely nifty in theory, actually applying Streetview to pinned images proved incredibly difficult for a technologically challenged individual such as myself and my partners, requiring a level of skill and precision beyond our own.

Other than these small quibbles, however, incorporating HistoryPin into our Resurrection City experience definitely helped to enhance our final product with an interactive, digital component. After completing the project and finishing the collection, I can say with confidence that the new media methodologies and foundational principles of digital history acquired over the course of the semester certainly proved beneficial both in completing this project, but also the larger Practicum project as a whole.

Links & Stuff

Check out the entire Resurrection City HistoryPin collection here.

To see Joanna’s Poor People’s Campaign HistoryPin tour, click here.

For an bibliography of source material we used for the project, here’s our Zotero group library.

An Endnote

Thus ends the semester and, with it, my requirement to post on this blog every week. Thanks everyone for taking the time to read my ramblings, it’s been real.

Happy Summer and Happy Trails!

Recent Comments