What in the Wordle?

A few posts ago, we examined the concept of culturomic analysis and explored the Google Ngram Viewer, a digital research tool that uses a document’s text patterns to link various lingual trends with specific historical periods. Not the only word-based tool in the shed (so to speak), the Google Ngram Viewer is one among several similar culturomic platforms available on the web.

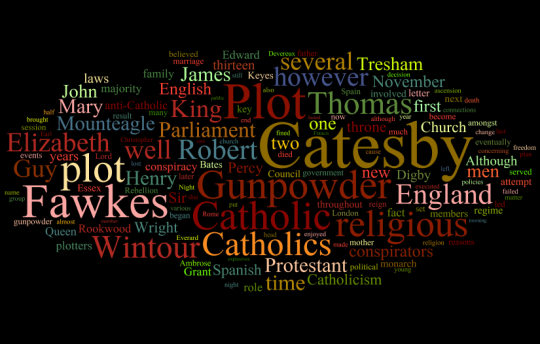

One such alternate tool is Wordle, a “word-cloud” generator derived from the input of text, giving “greater prominence to words that appear more frequently in the source text.” Whereas the Google Ngram tool matching lingual patterns in written documents with historical events and trends, Wordle serves more as a means of determining a specific document’s major themes and features.

To test the generator’s efficacy, I uploaded an old research paper of mine discussing the circumstances surrounding England’s 1605 “Gunpowder Plot” and subsequent annual Bonfire Night celebrations commemorating the event.

Behold, the visually-appealing result:

On the whole, Wordle proved relatively successful in conveying the document’s key themes. Looking at the generated word cloud, we can get a general grasp on the individuals involved, with the two most prominently associated with the plot (Sir Robert Catesby and Guy Fawkes) whose significance is accurately reflected through their placement as the two largest (most frequent) words. The plot’s religious connotations (along with those surrounding the ensuing holiday celebrations) are similarly highlighted. Surprisingly absent, however, are any references to the Bonfire Night celebrations following the events of the plot, on which a significant portion of the document focuses.

Additionally, several very common words (“although,” “new,” “well”) are given precedence within the cloud, along with a fair number of common names (“Robert,” “Elizabeth,” “John”) and word variations (“Plot” vs. “plot,” “Catholics” vs. “Catholic“).

Despite these nuances, Wordle still serves as an effective means of tracking a document’s language patterns and highlighting its primary themes. The platform’s personalization features add to its appeal, and include numerous options regarding font, cloud layout, and color scheme.

On the whole, the Wordle cloud-generator offers users an entertaining, personalized experience in obtaining a general representation of a document’s contents and main ideas. The application works best as more of a starting point in the research process, however, with users seeking a more in-depth analysis better served doing supplementary studies elsewhere.

Recent Comments